Educational research - how can we measure complex systems?

Middle management, in a recent personal development session, was introduced to the research of John Hattie on effective teaching strategies in his publication visible learning. In essence, Mr Hattie advocates that through the meta-analysis of thousands of educational research papers, certain interventions are more effective in the classroom than when compared to others. I have in previous posts linked to his research in support of certain teaching techniques like direct instruction.

However recently, my colleague Ximena brought to my attention some admissions around his methodology by Mr Hattie and with further reading of primary literature problems began to emerge. The aspect of Hattie's research that is being brought to the fore by policymakers and prominent educationalists is the effect size. A number greater than 0.4 is a highly effective intervention in the classroom as seen from the above chart.

So how did Mr Hattie come up with these effect sizes? Norwegian researcher Arne Kare Topphol has written: "Can We Trust The Use of Statistics in Educational Research" that investigated the very nature of educational research and the conclusions that such research reaches. He was particularly critical of Hattie's analysis.

Now to delve into some statistics! The effect size is related to the common language effect size which is the probability that a score selected randomly from one classroom will be greater or less than a score selected randomly from another classroom. Once we have the values from the two classrooms, you divide the difference between the two means by the square root of the sum of their variances and then determine the probability associated with the resulting z-score. Having now looked at the primary research the last step of converting into the probability using standard normal distribution tables was not done, so the values generated are not relating to a normally distributed population of students.

John Hattie himself admitted that the numbers his meta-analysis generated are in error in earlier versions of his research, which has been amended in later publications and was more representative of standard populations.

"Thanks for Arne Kåre Topphol for noting this error and it will be corrected in any update of Visible Learning."

However, another more important problem emerged as I delved deeper. Notice in the above diagram that one population is being compared to a control group, where a variable has been changed and others held constant. Hattie sometimes uses "effect size" to mean "as compared to a control group" and other times uses it to mean "as compared to the same students before the study started."

This ambiguity makes hard if not impossible to compare different effect sizes. The comparison of these "effect sizes" is absolutely central to the analysis. Comparing effect sizes is pointless if the effects are being measured against dramatically different comparison groups.

But this a central problem with educational research. When conclusions are generated are they valid due to the complex nature of the population it is inquiring about? Niaz (2009) concluded that as all observations are theory-laden, it is preferable that interpretations based on both qualitative and quantitative data be allowed to compete in order to provide validity to the research. Furthermore, that there are ‘degrees of validity’ as both validity in the quantitative sense and authenticity in the qualitative sense, ultimately depend on who is participating in the research. Critically, generalising of the results obtained from qualitative studies is not desirable. In both qualitative and quantitative research generalising is possible, provided we are willing to grant that our conceptions are not entirely grounded in empirical evidence but rather on the degree to which it relates to those involved in the research. Formulation of hypotheses, manipulation of variables, and the quest for causal variables was considered by many teachers to be equivalent to the scientific research and reduced complexity.

I think is the major problem still, is this last point the researcher made. How to deal with the complexity that is inherent in our profession. An approach called safe-to-fail experiments is one possible way I am investigating various contexts that might help nudge a complex system like a classroom or school community to behave in different ways. Although understanding a complex system is challenging, if not impossible, a safe-to-fail experiment might allow educators to simplify such systems in a more manageable way.

Cynefin, pronounced kuh-nev-in, is a Welsh word that signifies the multiple factors in our environment and our experience that influence us in ways we can never understand.

As an example, I identified the context in which I would like to act or where I had influence, say changing the arrangement of desks in the school. I then narrowed that context down to a manageable group (my classroom). To do this, I considered the following:

- What is the boundary of my community? What designates someone as in or out of my community?

- Who is involved in my community? How do these people interact? What is the nature of their interactions?

- How can I physically represent my community? How could I play with representing my community in different ways?

It turned out that in doing this there was a very little emphasis on the people in the community, with a much greater focus on the overall shape of the community and what happens between the people in the community. It became something like as a school of fish, acting together but independently to create an overall effect. The interactions between the fish leading to an overall change in direction or shape.

- I revisited what I would like to see more of or less of in my community. e.g. I would like to see more active collaboration in my classroom.

- I created a list of possible simple experiments that I could carry out in my community. This needed a fair bit of thinking and some refining as my experiments needed to follow the following criteria:

- The experiment is just as likely to fail as it is to succeed.

- The experiment does not need permission from anyone to be carried out.

- The experiment does not need resources out of my direct control allocated to it (e.g. money).

- The experiment can be shut down immediately if unsuccessful, or leading to a negative response from the community.

- The experiment could be amplified if the community responds positively.

- I was able to carry out multiple experiments at the same time.

- I did not know how my experiment is likely to impact the community, if at all.

- Did anything change? What? What could this tell me about the community?

- Did anything stay the same? What? What could this tell me about the community?

- Did anything expected or unexpected happen? What? What could this tell me about the community?

So after my attempts at safe to fail experiments, where does this leave me with Hattie? With these new interpretations in mind, I reread visible learning. The major argument underlying his analysis relates to how we think as educators. It is a mindset that underpins our every action in the classroom. it is a belief that we can impact learning through evidence.

Hattie does not view his meta-analysis and effect sizes as ends in themselves, and states.

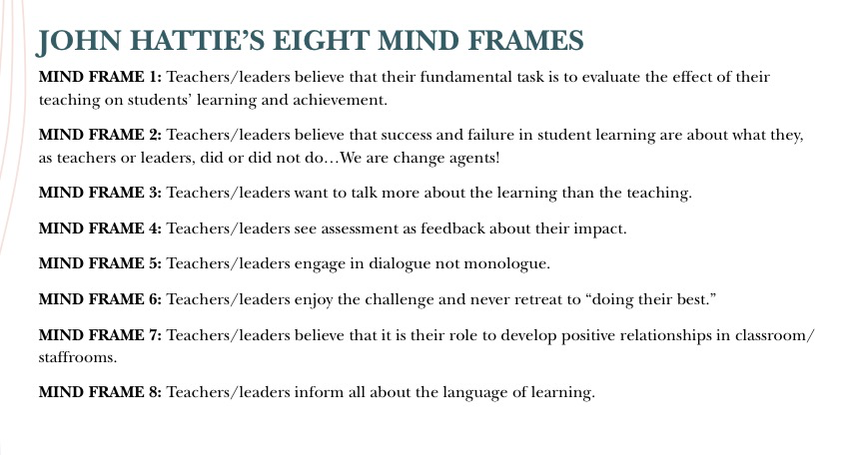

"I used to think that the success of students is about who teaches where and how and that it’s about what teachers know and do. And of course those things are important. But then it occurred to me that there are teachers who may all use the same methods but who vary dramatically in their impact on student learning"This observation led him to identify eight mind frames that he says characterise effective teachers:

Although derived from some of the most academic of research, these mind frames suggest an approach to teaching that is very context driven and flexible, driven by adopting a more conscious approach to our work as teachers and a more deliberate effort to obtain student voice about the impact we have on their learning. In summary: Know thy impact.

References:

Niaz, M. (2009). Qualitative methodology and its pitfalls in educational research. Quality & Quantity, 43(4), 535-551.

Comments