Can you Passively Learn?

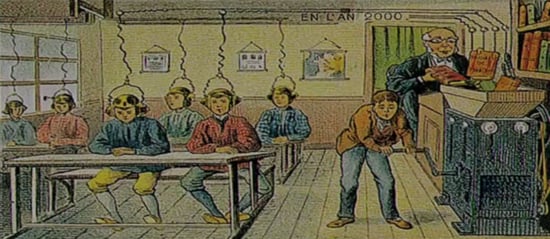

While scrolling through my social media feed, I came across the following diagram that a fellow educator I follow had posted.

Such data is often used by educators and it is still all too common to see images such as the one above even though they are not actually true and have no basis. We all easily copy and paste such simple infographics. This ease of transmission has made it easy for false ideas to become truth. It is important, that we as educators critically evaluate what we post in order to effectively role model to our learners.

The graphic above has many flaws, two of which I will highlight. The image claims that people only remember 10% of what we read but can remember 90% of what we do. The idea is not new and is often cited as evidence for moving away from more didactic teacher-led 'traditional' teaching and towards more student-centred 'progressive' teaching. Such claims challenge educators to think about the impact of how they teach has on their learners.

If these numbers were indeed true, then the findings would have a major impact on the way we teach. It would lend weight to the argument to move away from teacher-led instruction to more experiential teaching methods. However, are these numbers actually based on any evidence? If not, should we develop more experience based teaching approaches anyway?

Within the last few years, many educational researchers have been citing these percentages as a justification for their ideas. So, of course, educators before just accepting such numbers would have actually read the source material. Well, if you say a lie often enough it becomes the truth, or so the saying goes. The most often cited source for the data is from Edgar Dale’s 1969 book Audiovisual Methods in Teaching. The context of Dale’s book was with the teaching of film in classrooms, advancing a theory that audiovisual materials were essential for teaching film appreciation and that more generally, reading and listening should account for a smaller portion of educational instruction as opposed to practical applications in a film studies classroom.

However, the original diagram used, which he called the Cone of Experience, had no data to support his ideas. In fact, Dale wrote himself that the cone was:

“…merely a visual aid in explaining the interrelationships of the various types of audio-visual materials as well as their individual positions in the learning process/ The cone device, then, is a visual metaphor of learning experiences, in which the various types of audio-visual materials are arranged in the order of increasing abstractness…and abstraction is not necessarily difficult.”

So, if the author of the original citation saw the visual aid as a visual metaphor without hard data, how have so many in the education come to believe that learners will only remember 10% of what they read?

The data traces back to a WWII Colonel named Paul John Philips who included the statistics in reports for the Navy and the petroleum industry. Scholars who have also looked into the findings have found that data was most likely,

“…a rounded-off generalization based on Philips’s experience/despite its widespread dissemination among scholars of all stripes, there is no more conclusive evidence of the data’s validity than that.”

So despite no evidence for the numbers proposed, why does the myth continue to appeal to educators? Maybe cause even though there is no direct evidence, it just seems right. For those more 'progressive' educators who believe the education system is antiquated and based on a factory model churning out robots, they believe strongly that hands-on, interactive, participatory learning engage learners on a deeper level and help them understand the subject matter better. We all have our own intuition and anecdotes to support our beliefs. So naturally we like anything that tells us our methods of education are the best for learning. The scientific term for this is confirmation bias, or “the tendency to accept evidence that confirms our beliefs and to reject evidence that contradicts them.

So for those more 'progressive' teachers out there, even if the data often used to simplify Edgar Dale’s cone of experience has been debunked, it still leaves us with an important question: Was he wrong in his base assumptions? A critical aspect of Dale’s cone of experience has been confirmed by additional studies into learning and brain functions, namely that different approaches can “influence the efficiency in learning.”

So for those more 'progressive' teachers out there, even if the data often used to simplify Edgar Dale’s cone of experience has been debunked, it still leaves us with an important question: Was he wrong in his base assumptions? A critical aspect of Dale’s cone of experience has been confirmed by additional studies into learning and brain functions, namely that different approaches can “influence the efficiency in learning.”

In the 1980s, Arizona State University professor David Hestenes published results of a study done on learners studying physics. For the study, he asked learners across a broad range of didactic courses to answer questions about the physics concepts being taught, and the results were shocking. According to the results, most people who take lecturer-led lecture courses don’t attain a good understanding of the fundamental concepts of physics.

According to Hestenes, learners have to be active in developing their knowledge. They can’t passively assimilate it. That idea would seem to support Edgar Dale’s fundamental idea of doing versus reading as being the most important for retention of information, and Hestenes actually had the data to prove it. Of course, understanding the basics of physics is in itself very different from other subjects like history or language. Which is why researchers of the past decade have started to embrace new, more complex theories that work to address different methods, different subjects, and different learners.

The second point of the graphic is the misuse of the terms active and passive learning. The term “passive learning” is an oxymoron. There is no such thing. If our learners are indeed learning, then they are NOT passive, and learning does not always include a physical act of moving for example.

Engagement and learning is an exercise of focused thinking. Without mentally focusing on what you are learning, there can be no learning. The idea of passive learning vs. active learning through the outward expression of engagement is not a useful one. A learner can look ‘active’ with their learning because they are talking with others, but without assessment of the learner’s cognition, we cannot know if learning has occurred. On the other hand, a learner can appear ‘passive’ in their learning because they are quietly reading; not in a collaborating in a group or exhibiting more extrovert behaviour. In both instances, the learners may or may not be actually learning.

Learning cannot by definition be mentally passive. If we are talking about actual growth in understanding and not just a viewing of learners performing a set task, the idea of passive learning doesn’t exist. It must be active, cognitively active. If you are passively learning, you are not learning at all.

Comments