Fake future news

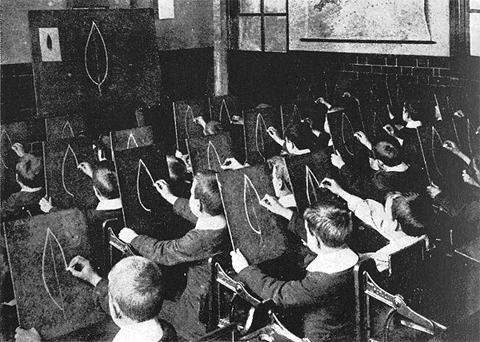

I have been to a number of ed-tech conferences over the years and the vast majority of speakers discuss with the righteous indignation of Ken Robinson that today's education system is a school-as-factory scene represented by images from 19th century classrooms. The majority are romantic about a future of education, one more 'personalized' through automation, based on algorithms; yet see no irony in creating creative classrooms from automation. They believe that through the power of technology, the kids will be alright.

However, I am a science teacher and I do love evidence. So as I have listened to these speakers, I always ask is this true? One skill that we desire to develop in our learners is critical thinking, one important aspect of thinking critically is recognizing confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that affirms one's prior beliefs. Having now been to these conferences, confirmation bias can be seen is the way attendees create narratives to explain the necessity of technology and the promises of what technology will bring to our learners. However, despite a recent drive in the world of education to be "data-driven", much of claims I have been hearing from the ed-tech community are quite fanciful.

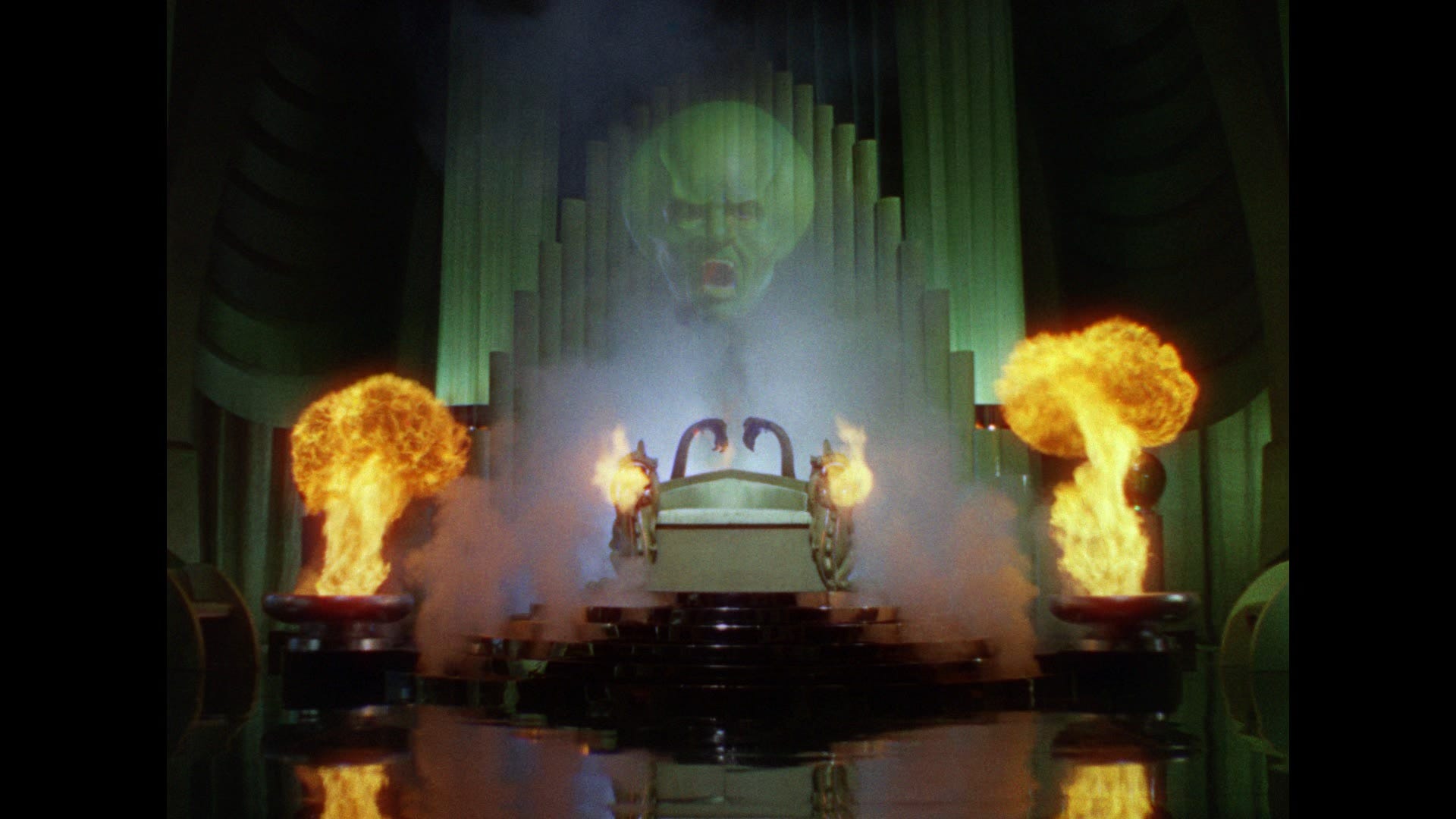

One popular idea running through educational technology is the concept of personalized learning. Based on the ideas of Psychologist B. F. Skinner who believed machines could be used to train people. In this approach, it is the machine, not the learner that is being taught. In order to personalize the learning, the machines must be taught through conditioning and training algorithms to elicit optimum learning behaviors for the learner. This reduces our students to merely conforming robots. This is my great concern with much of education technology: not that "artificial intelligence" will, in fact, surpass what humans can think or do; not that it will enhance what humans can know; but rather that humans -- intellectually, emotionally, occupationally -- will be reduced to machines. Education should be an exciting and unpredictable adventure in human enlightenment. This reduction is seen when we talk on the phone with customer support. Humans being bent towards the machine.

The common themes around education technology and 21st Century learning focused on developing generic skills are narratives about the inevitability of technology and how it will affect our future working lives. These narratives are reinforced by the following "facts' that I consistently see and hear in presentations.

The problem is, none of these stories are actually true. We do not know what the future holds; we can build predictive models, sure, but that's not what these are. Rather, these lies get told to steer the future in a certain direction, to create the outcome of the statements. As Hitler's propaganda minister said:

“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it"

Many of these stories contain numbers, and that makes them appear as though they're based on research, on data. But these numbers are often cited without any sources. There's often no indication of where the data might have come from.

Take the claim that "65% of children entering primary school today will end up in jobs that don't exist yet." It is a quip made by President Bill Clinton in 1996. It's not a fact. It's a slogan. The "half-life of skills" claim seems to have a similarly dubious origin. We have to keep retraining ourselves, so the story goes because people no longer remain on the same job or in the same career, so we have no need to form unions and demand better conditions as our time in one job will be fleeting. But is this the last assumption of people changing jobs more frequently than they ever have before, and they're doing more different kinds of work than they ever have before, true? Well, no. Not in the largest economy on the planet, the US at least. Job transitioning has actually slowed in the past two decades. While the types of jobs we do have changed substantially in the last century, the speed of new types of jobs has also slowed since the 1970s. Despite all the rhetoric of the "gig economy" of freelance uber drivers and Air B & B owner-operators, around 90% of the workforce is still employed in a standard job and this % has not changed much since 1995.

So finally, is technology changing faster than it's ever changed before? It might feel like it is, but many historians suggest not. Robert Gordon has been arguing for a long time against the techno-optimism that saturates our culture, with its constant assertion that we’re in the midst of revolutionary change. Developments in information and communication technology, he has insisted, just don’t measure up to past achievements. Specifically, he has argued that the digital technology revolution is less important than any one of the five Great Inventions that powered economic growth from 1870 to 1970: electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine and modern communication. Gordon argues, most digital technologies are consumer-based and small incremental changes on what has come before, and these have not necessarily restructured our world. We may be compelled to buy the newest phone every year, but that doesn't mean that technology is changing faster than it's ever changed before. Machines don't drive history; people do. We must be cautious, technology should be a tool we use to become a better society, not one which enslaves into a preordained narrative.

Comments